Out of the Matrix 2.0

HKOPENPRINTSHOP Hong Kong 2019

Marian Crawford Andrew Gunnell Richard Harding Clare Humphries Ruth Johnstone Rebecca Mayo Jonas Ropponen Andrew Tetzlaff Curators: Richard Harding Wilson Yeung

Out of the Matrix

RMIT Gallery Melbourne, 2016

Jazmina Cininas Marian Crawford Lesley Duxbury Joel Gailer Andrew Gunnell Richard Harding (curator) Bridget Hillebrand Clare Humphries Ruth Johnstone Andrew Keall Rebecca Mayo Performaprint Jonas Ropponen Clare Humphries Ruth Johnstone Andrew Keall Rebecca Mayo Performprint Jonas Ropponen Andrew Tetzlaff Andrew Weatherill Deborah Williams

"Triggering concepts of reproduction through notions of original and copy, sameness and difference, real and virtual... on and on we go down the rabbit hole." Richard Harding, Curator

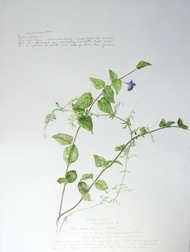

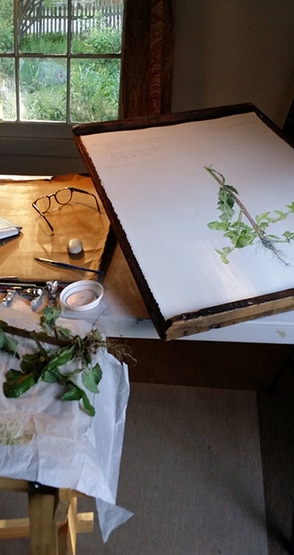

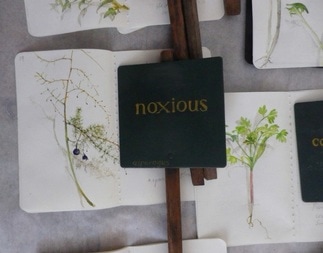

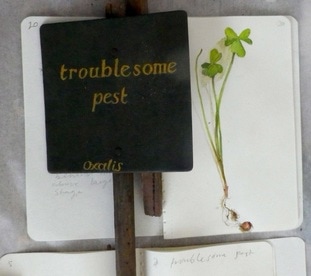

The Weed Census Project 2015-2016

Fremantle Arts Centre

As a method for observing the spread of weeds and their impact on landscapes, I began The Weed Census Project in Fremantle in April and May 2015 (continuing in November 2016) to capture a localized sample of the status of weeds. The Project is based at the Fremantle Arts Centre and extends beyond its walls into the City as the adjoining parks and verges have an impact on site management within the Centre’s walls. A laboratory was established next to the Arts Centre galleries and for five weeks I was actively and visibly at work archiving specimens and making botanical studies during opening hours. One day was set aside through the Open Studio program where interested visitors were invited to add to the collection.

Current weed texts and websites concentrate on either the noxious and poisonous, garden escapes and more recently a revived interest in foraging and use of herbs. A century ago the assessment of weeds was driven by agricultural and food supply needs. Just over 100 years ago in Western Australia, 11 plants were proclaimed noxious with a further 4 listed as noxious, 12 were described as poison plants with an additional 7 said to be poisonous (but not gazetted).[1] In 2015, amongst the now extensive Noxious Weed List for Australian States and Territories there are in excess of 100 prohibited species amongst the extensive listings for Western Australia.[2]The colonial era language of weed documentation also says as much about plant migration as revealing attitudes to human migration. As an art project I draw on the colonial historical language of weeds to embrace a broader context for the complex and difficult management of both plant and human migration.

Ruth Johnstone’s project is supported by the Fremantle Arts Centre’s Artist in Residence and Open Studio programs and RMIT University’s School of Art.

[1] Noxious Weeds and Poison Plants, Illustrated for the Guidance of Settlers, Government Printer, 1910.

[2] Invasive Plants and Animals Committee, January 2015.

Media: watercolour on paper, acrylic paint on metal, plant specimens

White Library at the Athenaeum Library, Melbourne, 2015

for Nite Art and Rare Books Week 2015

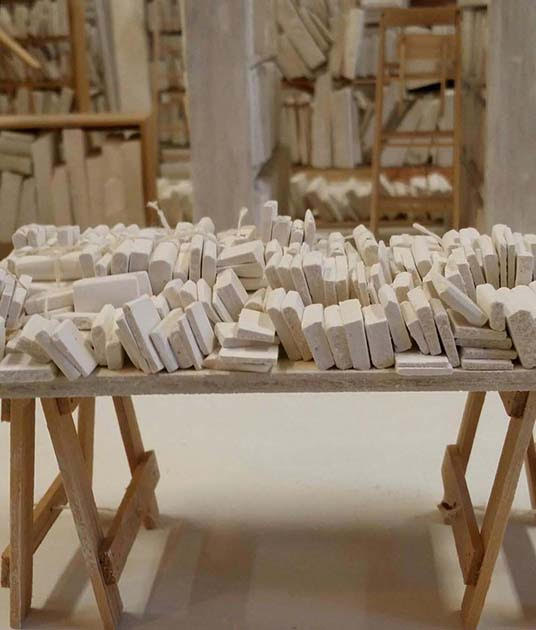

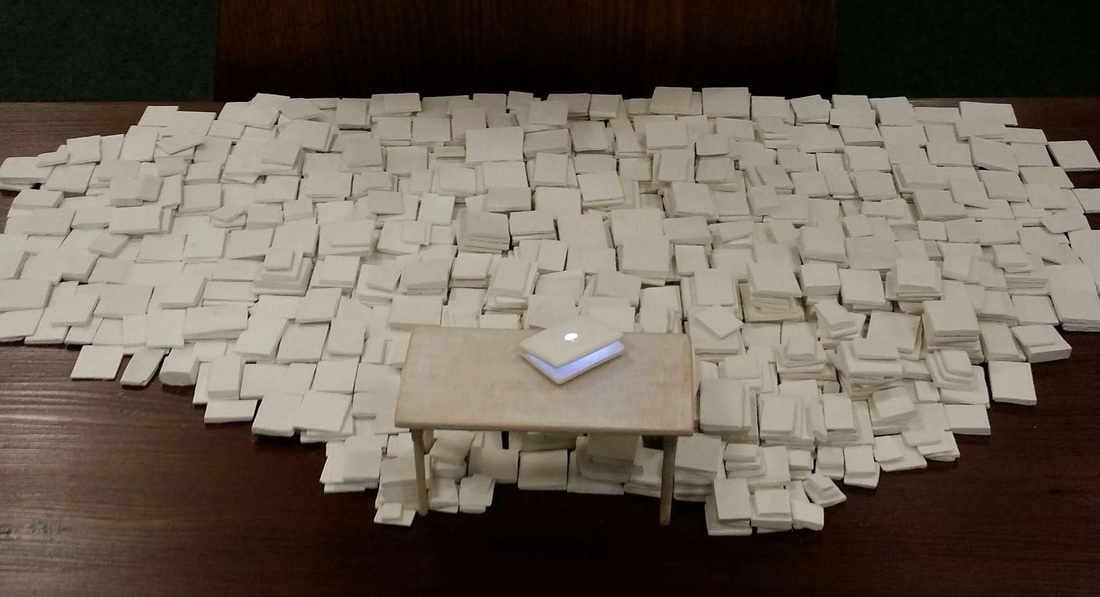

White Library presents a tabula rasa - literally, blank tablets -as repositories of future information or, indeed, a lost body of knowledge, miniaturised and compacted. The micro-installation, tucked amongst the bookshelves of the Athenaeum Library, sets up a nexus between the arcane tablet, the hard copy book and a laptop, but they are neither one. This project, housed to its own minute scale amongst the existing library shelves, also offers reflection on the compression of knowledge and the written word and the function of a library in the digital age.

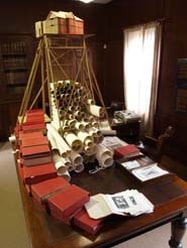

Mining the Archive

LARQ artist residency and installation at Queenstown Mining Museum, Tasmania 2012

Curator: Raymond Arnold

‘Everything is so jumbled up in this overstocked house (I mean only my

own “treasures”!) that things are not easy to get at, and if you so much

as touch any one thing a pile of others may tumble about your head.’

Robert Sticht describing Penghana in a letter to Mr Robertson,

November1911.

The high-hipped profile of Penghana, designed in 1897 as the Mt Lyell Mining and Railway Company manager’s residence, appears to match the surrounding hills of Queenstown. As an engineer and later a mine manager for the Mt Lyell company, Robert Sticht applied his propensity for moving mountains to build a comfortable, if overfilled home for his family atop a pyramid shaped hill, the plateau scraped to the smoothness of a billiard table. It was a home for connoisseurship and intellectual pursuits, supported by a vast collection.

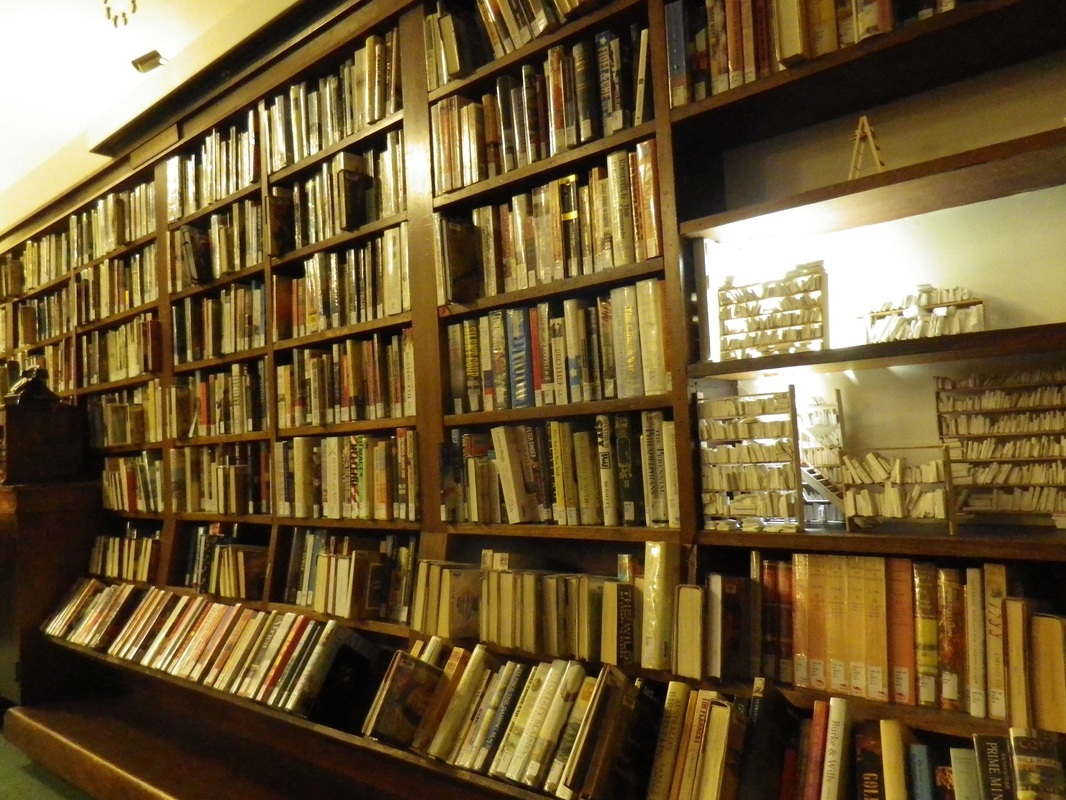

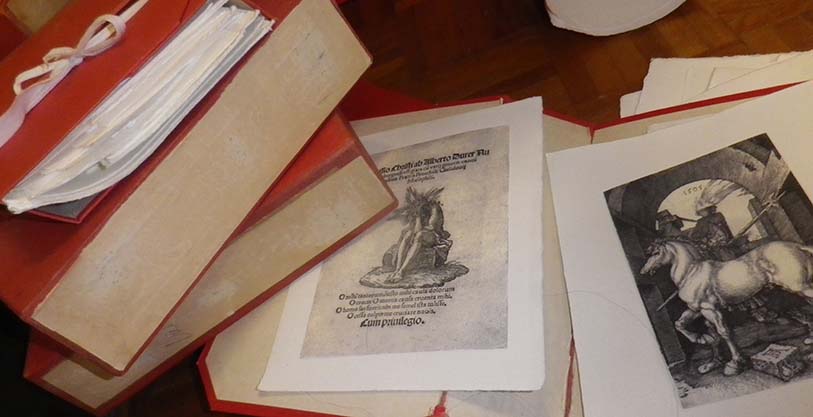

Being an artist is to be the keeper of a lifelong practice so there’s a guilty pleasure in indulging in another’s collection without the burden of having to store and care for it. Sticht’s legacy provides the background material for my fleeting and piled up intervention in his former office. Understanding how mining and art are interdependent is a broad and perhaps unexpected enquiry. At Penghana engineering comes to the party in providing a home where the intellect and knowledge of the arts could be nurtured. It’s possible to see the development of the Sticht household by examining the architectural plans and photographs of Penghana, including the extraordinary ghostly spectre of a windowless house shell with exposed roof trusses in the Galley Museum, Queenstown. The haulage track shows how the locally made bricks and timbers were dragged up to the flat top mount against a stark and raw background landscape. This pictorial evidence assists me in literally building a timelapse based architectural model to shape my understanding of history. Sticht’s vast art collection was matched by extensive libraries, housed both at Penghana as well as the Mt Lyell mine manager’s office which was built in 1904. It was mining that brought Sticht to Queenstown and it was mining that could afford lavish spending on art and books. Not so much a collision of unconformity at the scale of geological history, nevertheless there is a collapse together of mining and connoisseurship on an ambitiously heroic human scale. Sticht’s print collection was accompanied by a carefully annotated inventory. His print ledger is now housed in the State Library of Victoria and most of his prints are in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. Woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer were among his favoured works, and 50 Dürer prints were given priority listing in the ledger of well over a thousand 16th to early 20th century European works along with a smattering of Australian prints. Prioritising Dürer’s prints confounds Sticht’s alphabetically organised listing in his index. Authentic Dürer prints are identified as such and with accurate connoisseurship, facsimiles are also noted. While Sticht ascribes the Small Passion as a facsimile, he has also collected at least one authentic print with the same title. The facsimiles would have been highly useful for comparative study, particularly with his set of the Large Passion and for more fully comprehending the religious narrative cycle. Sticht’s art books were among his detailed accession lists, coded and ordered in 100 (book) cases. His art book collection, particularly those focussed on prints, matches any reference section in public institutions of his time. Sticht had no less than two libraries in his house (with bookcases spilling out in other spaces) and they contained his folios of prints, boxed in gold embossed leather casing, presenting as faux books. The smaller library, the couch comfortably jammed in, is a cabinet of curiosities itself, a wunderkammer only for those to enter who showed sufficient interest for Sticht to reach up for a box containing Dürer prints. Sticht’s remarkable collection of artwork cannot

be reasonably brought back to Queenstown. One Dürer print alone can be valued at half a million dollars. I take Sticht’s lead in using facsimiles for the purposes of celebrating his life of engineering and art, reinstating his passion for collecting and installing it at the managerial heart of the Mt Lyell mine, where the last vestige of Sticht’s Queenstown library remains. In mining Sticht’s archive I am attempting to connect multiple aspects of his life, colliding compressed scale with life size, a gathering of home and work, an exchange of ore for art.

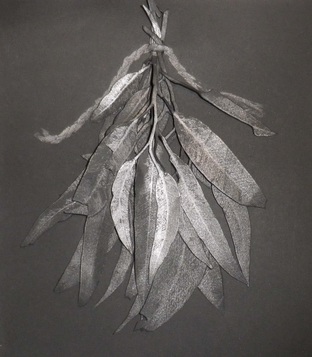

Eucalypt Project 2013

in Paper Nights: Daniel Agdad, Alexis Beckett, Anne Kucera, Ruth Johnstone, Megan Keating, Julia Silvester

MARS galleries Melbourne

The Alpine region of Mt Buffalo has been pivotal to the 7 years of work leading to 2013. I have documented fire recovery of the landscape through printing from and reconstructing prints from eucalypt leaves into garlands and as leaf litter using the leaden palette as a memorial to loss. Samuel Beckett’s perception of the end of nature is delivered as a human construct in Endgame and is the closest literary experience I can find that relates to living in an ash black landscape for weeks on end.

Proudly powered by Weebly